Cybersecurity Superheroes Next Gen: How Higher-Ed Helps Them Find Their Crime-Fighting Niche

- 0.5

- 1

- 1.25

- 1.5

- 1.75

- 2

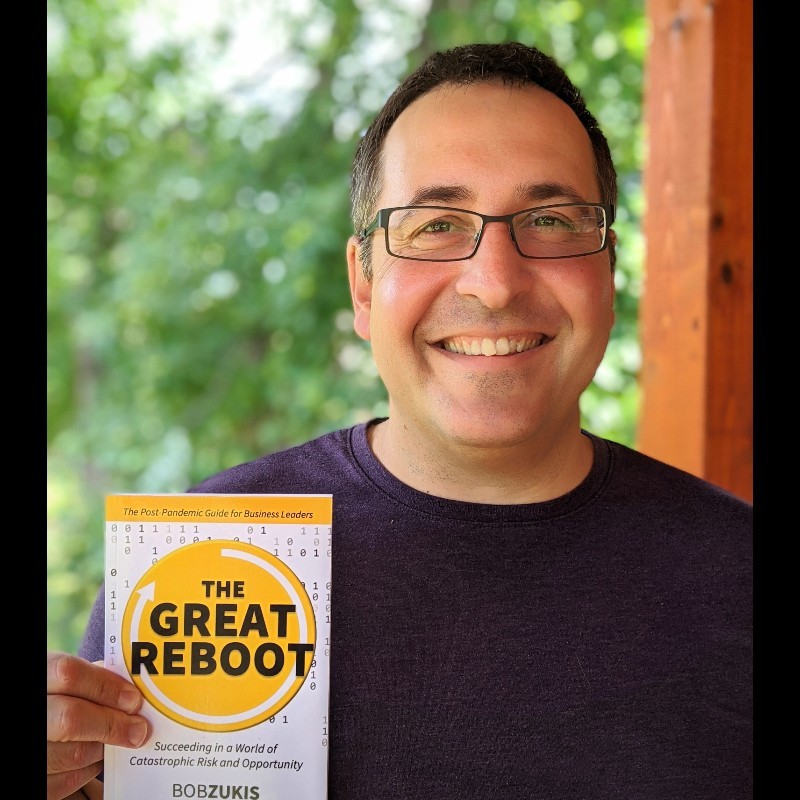

Mitch Mayne: Before most of us enter the professional world, we finish high school and go on to college and even graduate school in some cases to help hone our talents. But where do cyber criminals learn their skills, and is our education system up to the task of keeping young cyber minds on the right side of the law and training the next generation of workers to help thwart cyber crime? In this episode, we sit down with Chris Veltsos, an Information Security Professor at Minnesota State University and an industry veteran with more than 20 years in cybersecurity. Chris is also the author of a new book, The Great Reboot, about succeeding in a world of catastrophic risk and opportunity. In addition to talking a bit about his book, Chris tells us what it's like to teach the next generation of cybersecurity professionals and talks about what education is getting right and wrong. I am Mitch Mayne, and you are listening Into The Breach. Chris, I miss you, man. It is good to hear your voice. And you have a fairly recent book out called The Great Reboot. Tell me what the book's about.

Chris Veltsos: The Great Reboot is a book about systemic risk and what do we do about them, and yet making sure that the book doesn't end up being all doom and gloom and instead, also point out the blue oceans in a way that are accessible when companies manage to align their digital risks and end up taking the right kinds of risks to be able to capture some of the opportunities that are out there.

Mitch Mayne: You mentioned something there that I kind of wanted to poke on a little bit in there. It was in our list of questions. Flashback to 20 years ago. This was an industry that was still pretty much in its infancy. I know it may be a little more or less than two decades ago, but you get the idea here. I feel like you and I have kind of grown up in the industry. How did you come to be a professor focusing specifically in this niche and a prolific author on the subject?

Chris Veltsos: For me, cybersecurity in a way was always there even when I didn't know or didn't realize that it was going to be the path that I would eventually move towards. In part, it's because I was exposed to some viruses in the late eighties, early nineties while I was a student learning about computer science. Cybersecurity material was very technical in focus and frankly the impact on the business had not yet been felt. There were some disruptions in part because some of these early viruses would be timed to detonate and end up damaging databases or end up overriding boot sectors on hard drives and such, but those were still fairly limited in terms of scope and impact. For me, my shift of focus from the software engineering, computer networking happened around the mid 2000s when my institution gave me the opportunity to do a sabbatical. So I had been teaching for seven plus years. I put on some jeans back and donned a backpack and went back to school and studied information assurance. And frankly, I've never been able to look back on just pure computer science since then because it opened my eyes to the possibilities and the need for cybersecurity. So I try to translate this into my classes today, making sure that I spend the time so that the students understand that cybersecurity exists not just because of the spooky things, but it exists to enable the business to stay in business and enable the business to take on the right amount of risks that are necessary in order to compete in today's marketplace.

Mitch Mayne: Let's talk about your classes. I don't have purview into your actual curriculum of what you're teaching. So tell us what you're teaching currently and how you get your information and a little bit about how you stay current with the cyber landscape because it's changing exponentially.

Chris Veltsos: In terms of the classes that I teach about 12 plus years ago, I developed at the undergrad level some cybersecurity courses for our department. Initially, it was for students that were more traditionally focused towards software development but also had curiosity and interest in doing more connected to cybersecurity. At the undergrad level, there was a sophomore level information security principles, so very business focused. And at the time I didn't realize how much that was the right approach, especially for students that are much more technology focused and therefore content focused for them to understand where their paycheck comes from and the role that information security plays in making sure that they get paid. Then after developing some of these courses at the undergrad level, I also started dreaming about initially and eventually developing a master's degree program. And for that I had the option of doing something more technical, perhaps something with a lot of cryptography type courses and very deep connections to the hardware or to mathematics. And instead I went much a closer route to the world of business. And instead we did come up with a graduate degree program information security risk management that really connects the world of technology and the world of risks with the world of business. So we are actually leveraging some courses from the MBA program and we are also teaching some courses around how to communicate with executives.

Mitch Mayne: Well, that sounds like a pretty holistic approach, which is something that we desperately need once the youth actually enter the workforce is that holistic view of IT is no longer the sole domain of cyber. It belongs in every aspect of the business, and you mentioned it earlier from the board, to marketing, to PR, to HR, to IT. As a general rule, not speaking specifically about your university or your students, do you think students are prepared for cyber careers when they leave the university or are they still coming in pretty green?

Chris Veltsos: I want to make some parallels in a way between the field of cybersecurity and the field of computer science. Much like 10, 20 years ago, you had folks choosing or declaring as their path that they wanted to focus on computer science because they wanted to develop computer games. To me, the world of cybersecurity, from an incoming student perspective, there's still some misconceptions. So some of those students are coming in thinking that a degree in cybersecurity is going to make them some kind of super duper hacker. For some of them, that's really the draw because they have something to prove or they want to impress somebody. They're looking for that edge, which is almost an adrenaline edge of wanting to try to do something that very few other people can do. From an incoming student perspective, we have some progress to make to better explain the full breadth of careers that is available for people who are interested in cybersecurity. I'll give you a little bit more concrete example. Many, many years ago I had one of my undergrad students, this person wasn't doing well in one of their undergrad classes. In a way, they hadn't found their field. And then they started taking some of my security classes and realized that they were interested in cybersecurity, but not necessarily from the technical perspective. They didn't really want to go and run the normal kind of pen testing tools. Instead, they were much more interested in the policy and the governance space. So I had the flexibility within the classes that this person was taking to kind of work with them to angle some of the assignments and give them the room to develop themselves and their skills in that area. This person is now very gainfully employed.

Mitch Mayne: That's interesting that you should pull on that because I'm going to go there next and I wanted to make two points. Number one, your notion that cyber career is no longer limited to sitting in front of an IT computer and working in a SOC, but it does have policy implications. And if you look at somebody with my background who came in with political science and communication, I mean you wouldn't think that belonged in a technical world, but there is a need. In the episode just prior to this, Chris, we talked to a journalist who profiled two students, one was 12 and the other was 16. These were two youth who ended up getting in some legal trouble because they're playing around on the internet and doing so with astute hacking skills, breaking into some rather large institutions and getting caught and ending up in the hands of law enforcement. One of the refrains from these students was something that I hear and I think that you probably hear as well is these are really smart adept creative individuals who don't see themselves in a nine to five office job. They don't see themselves sitting in even a campus university setting traditionally as we know it. Do you think formal education in some ways hinders this sort of creativity that these people have? First part of the question is, if so, what can we do differently as academic institutions? And part two is what can we do differently as employers to cultivate these kids?

Chris Veltsos: You bring up such deep points and I think we're seeing how in terms of the global marketplace today and the challenge that organizations are having in attracting and retaining talent, I think we're seeing this play out not just in the cybersecurity world, but in the world of the workplace in general. In part, it's because at least in the past there have been very rigid paths that if you wanted to get a job in a particular field or in a particular organization, you in a way you had no choice and you had to follow this path. And post COVID, I think a lot of organizations are realizing that they need to be a lot more flexible in their hiring practices. One of the ways that I keep track of all the things that are going on in this field is I am very well plugged in Twitter and on LinkedIn, and one of the things that I see in both of those platforms is some of these job position adverts that list an incredible number of required qualifications. Some of them are silly. Some of them say, you want to be a cloud security engineer, you must have been working with the cloud for 20 years. Well, the cloud, at least with the word the cloud didn't exist 20 years ago. Both in academia and in terms of industry, in terms of organizations looking to hire and retain talent, we have to rethink our approach. We have to open up the paths that can lead to the organization and to the job. Then the other piece is something that I think you and I had talked about several years ago is perhaps even consider retraining existing folks that may or may not have cybersecurity background currently, and instead teach them some of these cybersecurity basics because you've recognized the rest of the skills that they bring to the table.

Mitch Mayne: What I sort of heard here was what we're experiencing is a little bit of a culture shift, a dynamic change from what people actually want from their own careers. Is this a symptom, do you think, of a larger shift in the workforce where youth are growing up and not wanting to be dad's nine to five or mom's nine to five and we want our own career that we can sort of build around our life? Or is this something different?

Chris Veltsos: From my perspective, it is much more of this realization of people being more picky about the kinds of jobs that they're willing to take home, how they're going to spend these hours, how much time do they need to report to the office versus some flex time that they can work from home or work from a coffee shop or work from the beach. Again, from my perspective, and I might be wrong or I might be looking at just some outlier values, this is happening as well with state government in terms of attracting and retaining talent. We have to realize that the choices and the pain that people put themselves through in the past, because there was simply no other choice, is no longer valid in the world today. I've seen people that were gainfully employed in cybersecurity and pretty much from one they did the next said, " I've had enough, I don't like this culture at work. It's not a supportive culture. There's some issues with diversity, equity and inclusion, and so I'm going to quit and I'm going to go find an employer that values those things."

Mitch Mayne: Well, I mean you're definitely on a point there. None of us have guaranteed jobs. It's like being a nurse or a physician now. It's like it's one of the few areas where you can actually pack up your bags on a Tuesday afternoon and by Thursday have a new gig if you're skilled and known in the industry and even if you're not known in the industry. But it's something where I think it's forcing the hand of business to change the way it thinks about how it handles its employees because we are dealing with an interesting sect here. I mean, if we look at the folks who work in X- Force Red, for example, here at IBM and my other friends who are hackers or even incident responders, the mindset that they bring to their job is very different. It's more the mindset of someone who would work in an emergency room versus work in an office where nine to five necessarily isn't where life is or life happens. Life could happen on a Sunday afternoon, but they do expect that flex time. So I think that there is cause for the work world to kind of shift what they expect in turn from their employers. We are talking about a group of minds with incredible computer inaudible and certainly interests, especially hearkening back to episode one where we talk to the author of that article. One of the other elements that he mentioned that seemed to be missing for these youth was mentorship. What is the role of mentorship in all of this? I want to talk to it both from a university perspective as well as a workplace setting because I honestly feel like listening to this journalist tell the story of these two kids, if they would've had the right mentors in place, they would've taken very, very different paths and not ended up in the hands of law enforcement.

Chris Veltsos: There's another word that comes to mind, which is the word coach. So in my mind, the difference between a mentor and a coach is a coach tends to work on probably a more shorter term basis, much likely less than six months, and aims to improve performance on some pre- established metrics. To me, the word mentor is much more of a fluid, more long- term relationship. And I've seen some definitions that say the mentor must have experience in the field that they're mentoring in or that really the mentor must have the best interest at heart of their mentee.

Mitch Mayne: Do you believe that?

Chris Veltsos: I believe that it's the second one because otherwise we have a chicken and egg problem. I mean, if everybody must have experience in something by the time they're allowed to be a mentor to somebody else, then we would really not have as many mentors as we need. What I really like about you bringing this up, and especially with respect to educating fresh talent in a way is every student should be able to point to somebody in the institution as somebody who cares for them and somebody that they feel comfortable sharing some of their successes and sharing some of their struggles. Most of the time from a university perspective, most of the time that should be something connected to the domain of expertise. So based on what we're talking about, connected cybersecurity. But it can also be about just life in general. I remember many years ago, one of my advisees came to see me early one morning and he had had an altercation with law enforcement and he was visibly shaken, and so he needed somebody to take the time to listen to him, to brainstorm some potential follow up actions that they could take and to basically put their life back on track. In my classes and with my students, I try to create an environment where it's quite challenging frankly, but it's a lot of fun where I try to figure out where each student is at currently and try to estimate the potential that they have to be pushed upwards, and then I try to nudge each one of them just the right amount to help them grow in that direction.

Mitch Mayne: It's interesting you should bring up somebody that cares about you. I think that is a really distinct and important point. As a professional in the career, knowing that I have somebody in my orbit, whether slightly up the food chain or as a peer who actually cares about me is extremely important, whether or not that person actually does the same kind of work that I do. And hearkening back to my own undergraduate years, the professor that I think I related to the most, he was an economics professor and you know how much I hate science, but it was a dismal science, so it sort of worked for me. As we know economics, the dismal science, because I am a bit of a cynic. So that part of me was definitely intrigued. Let's talk a little bit about, you mentioned a student that had an encounter with law enforcement. I'm not sure what the encounter was, but this brings up a good point. Looking back at the two youth in the article that the journalist profiled, we know how they learned their skills. It was kind of trial and error. So how do you think folks who tend to go towards the dark side, what happens with this cultivated talent, I guess is what I'm kind of getting at? How do they learn their skills and where do they take it if they're not really offered any path to the good side?

Chris Veltsos: I would say what happens to them in a way depends on luck. What happens to them might depend on the particular regional flavor of the judicial system. I have conversations with my students about a red line in the sand, and for them to always have an understanding of where that red line is and to make sure they don't cross it. It's a red line of ethics. It's a red line that as part of studying cybersecurity, students often end up using penetration testing tools. Some of these tools, if you point it at the wrong IP address, for example, it could end up scanning a government entity or it could end up kind of rattling the doors on a business, let's say, a healthcare entity and you don't want to take down their servers. I think it's important for us in terms of society to have discussions around what's acceptable versus what's not. And fortunately, we cannot always trust what we see in the movies to help us understand where that red line is. So in the discussions I have with my students, I make it clear to them that simply asking a classmate, if that's the only option, that's okay, but it's really not good enough. Ask another faculty member, ask me, ask a professional in the field, but don't just ask another young person who is also kind of exploring and might be just unable to stop themselves from clicking and getting the adrenaline rush of using some tools and discovering some things and then just continuing further and further down the rabbit hole.

Mitch Mayne: We did see that in the article, and I think this goes back to your point though. If there's a lack of mentorship and a lack of guidance and a lack of trust, knowing that there's somebody that cares about you and that you can confide in, we do have a larger risk of young people going down the rabbit hole on the darker side.

Chris Veltsos: Young people make mistakes. And unfortunately, we live in the world today, the mistakes that you and I might have done 20 years ago, because let's pretend we're young enough for us to be young 20 years ago, those kind of mistakes are forever recorded in the logs of the internet. So it's a much more unforgiving environment for young people today.

Mitch Mayne: That is definitely true. I work with my own nieces and nephews to remind them, it's like a selfie might seem like a fun thing to do now, but you put that on Instagram and I don't think your employer's not going to be looking at that when you start to get a job. So I do want to ask you, if you were to start, so let's pretend we're in Chris's own little world here. If Chris were to start a Hacker University or Veltsos University or University of Veltsos, what would your foundation be for these students? What would you start with? What would be included in your curriculum that you think is missing today? Most importantly, what social elements would be included?

Chris Veltsos: First I would start with creativity in terms of creativity and passion. What is it that they're interested in doing? Making sure that they're not just interested in doing it for themselves or for nefarious purposes, but that they're interested in the learning and interested in the sharing. That's something else I try to do with my classes is have students share and teach other students. I try to create an environment where I think of it as cross- pollination because I do not want to be the only subject matter expert in the classroom, and instead, I want to foster an environment where students are learning a little bit from me, but they're also learning from each other.

Mitch Mayne: What do you think is missing from coursework today that you would want to toss into your curriculum for Veltsos University?

Chris Veltsos: It's easy for students who are interested in technology focused domains or careers or majors to only want content, content, content. Most of the time it tends to be focused again on that technology. From having been a faculty member for over 20 years, I've seen this time and time again where we had some student groups compared to like an MIS club, so a Management Information Systems club or let's say, a marketing club or something, where they wanted to have meetings to network and to learn from one another. Some of the more technical minded students were always looking for more content. From a hacker university perspective, I want to see, again, more broad development of skills. Yes, we can have some tech talks that are about how to use tool XYZ to take over a system or even take over a mainframe, but there should also be lots and lots of opportunities for, let's do something like a Toastmasters, right? So extemporaneously speaking, let's do some things about ethics. Let's do some things about studying from the Greek philosophers and things like ethos BETOS logos. How do we present? How do we convey? How do we negotiate? How do we say, " I hear you," instead of trying to overpower the other person with, " I am right, you're wrong"? Which again, I've seen many young students do this.

Mitch Mayne: I like that. That sounds very holistic. So you've got a little philosophy in there, you've got a little social science in there, even some communication in there. Chris, I wanted to ask you, one of the things that we always talk about is if you could give two pieces of advice or one piece of advice to the youth out there who want to embark on a cyber career, what would it be? I'm going to change that question for you because I think you've got a different perspective and I'm going to make it a lot harder. There's going to be folks out there who listen to this who are already professionals in the field and who may have even more experience than me and you. There's not much to take for more experience than me, but even more experience than you. And they're probably sitting there thinking to themselves as like, you're right, this mentorship thing is missing. I remember my sixth grade basketball coach was the best thing that ever happened to me because he taught me X, Y, and Z. What advice would you give to someone who's considering being a mentor? Are there organizations that they can plug into?

Chris Veltsos: Some of the organizations that come to mind are organizations that should already be fairly well known to anybody in the field of cybersecurity, and they tend to all start with the word I. So we have ISSA, ISACA and ( ISC)2. To me, these are the three organizations that tend to have programs of outreach that are focused specifically on students and/ or focused specifically on kind of mentoring folks that are just now entering the field. In some cases, we're seeing folks entering the field that they have have 20 or 30 years of experience of a career already in a different field. So they're not necessarily young folks anymore, but in a way, they're juniors in the field in terms of entering this. I've seen some great work being done by all three of these groups. Again, ISSA, ISACA, and( ISC) 2 in terms of creating programs to do outreach, to do support to even in a way help train mentors. You don't have to go through, in a way, a formal program to do this as long as you have, in my opinion, the right approach, the right mindset, which is, this is not about you the mentor, but it's about what you bring to the life and the world of the mentee and how you help them accelerate their way into cybersecurity in a safe way and in a productive way. Back to your question about two pieces of advice that I would give students today. One would be it's not too early and it's not too late to be a mentor. Be a mentor to somebody else. And to me, there's magic. The moment you allow yourself to think of yourself as a mentor, because it forces you to think in a more grown up way. You are going to take somebody else under your wing. You're going to be responsible for their development, for making sure that they don't get themselves into trouble. So it can come very naturally because you're good at something, you're passionate at something, and the moment you identify somebody else that could use some mentoring along those lines, then it's a natural extension and it helps you connect with really, in my opinion, what's going to be your future self. So it's never too early or never too late, frankly, to be a mentor to somebody else. You do not need somebody to impose this and say, " You're going to mentor this other person." Instead, look for some of these opportunities and step up and take advantage of them. The other piece that I wanted to say is I've seen my fair share of students where the environment in a particular path that they had initially chosen wasn't the right one for them. So my biggest piece of advice there is if something feels like it's not the right avenue, it's very challenging, there's lots of friction, there's lots of roadblocks, don't give up. Instead, look for a different path. That's going to be an easier one, a better one for you. Sometimes that means that you're going to take the more scenic route, and so it might take you a little bit longer to get to your ultimate destination, but usually there's lots and lots of rewards that come with taking the scenic route.

Mitch Mayne: Well, Chris, thank you for being on Into the Breach. It was a pleasure to have you on here today.

Chris Veltsos: Thank you very much, Mitch.

Mitch Mayne: A special thanks to our guest Chris Veltsos for his time and insight making today's episode. If you want to hear more stories like this, make sure to subscribe to Into the Breach on Apple Podcasts, Google Podcasts, and Spotify. You've been listening to Into the Breach, an IBM Production. This episode was produced by Zach Ortega and Clara Shannon. Our music was composed by Jordan Wallace with audio production by Kiran Banerjee. Thanks for venturing Into The Breach.

DESCRIPTION

Criminals don’t seek degrees in cybercrime from universities. So where do they learn their skills? And what is the role of higher ed in helping keep smart minds on the right side of the law and preparing them to defend against attacks? Minnesota State University professor Chris Veltsos has more than two decades of teaching and mentoring the next generation of cybersecurity professionals. He unpacks what he teaches in the classroom, what he wishes could be taught, and what higher ed can do to help keep bright minds on the right track.

Today's Host

Mitch Mayne

Today's Guests